Distributed System - Important Topics - Part 3

Names, Identifiers and Addresses, Flat naming, Structured Naming, Attribute-Based namingPermalink

OverviewPermalink

- Names are identifiers for various things like entities, locations, and resources.

- The goal is to resolve these names to what they actually represent.

- Human-Friendly Names: How to structure names that are easy for humans to understand, such as in file systems or the World Wide Web.

- Example: World Wide Web, “www.google.com” is easier to remember than IP address like “142.250.191.46”.

- Location-Independent Naming: Finding a way to identify entities without depending on their current location.

- Example: DNS (Domain Name System), Resolves domain names to IP addresses, allowing you to access a website from anywhere.

- Attribute-Based Resolution: Resolving names by using attributes of the entity they refer to.

- Example: Database Query, Using SQL to find records based on attributes like “age” or “email”.

- Human-Friendly Names: How to structure names that are easy for humans to understand, such as in file systems or the World Wide Web.

Names, Identifiers and AddressesPermalink

- Name: in a distributed system is a string of bits or characters used to refer to an entity.

- Entity: something that is operated on using some access point.

- Entities: hosts, printers, disks, files, processes, users, mailboxes, web pages, graphical windows, messages,network connections, etc.

- Address: Name that refers to an access point of an entity.

- An entity may have multiple access points and addresses.

- Identifiers: Used to uniquely identify an entity.

- An identifier is a name with the following properties

- An identifier refers to at most one entity

- Each entity is referred to by at most one identifier

- An identifier always refers to the same entity (i.e., it is Never reused)

- Name resolution maps a name to its address.

- Name resolution is performed by a naming system.

- In a distributed system, a naming system is itself distributed.

- Naming system: a middleware that assists in name resolution

- Naming systems are classified into three classes based on the type of names used:

- Flat naming

- Structured naming

- Attribute-based naming

Flat NamingPermalink

- Identifiers are flat names

- fixed sized random bit strings

- does not contain any information on how to locate an entity

- good for machines

- How to resolve flat names?

- Broadcasting

- Forwarding pointers

- Home-based approaches: Mobile IP

- Distributed Hash Tables: Chord

BroadcastingPermalink

- Broadcast the identifier to the complete network.

- The entity associated with the identifier responds with its current address.

- Example: Address Resolution Protocol (ARP)

- Resolve an IP address to a MAC address.

- In this,

- IP address is the identifier of the entity

- MAC address is the address of the access point

- Not scalable in large networks

Forwarding PointersPermalink

- for locating mobile entities

- When an entity moves from location A to location B, it leaves behind (in A) a reference to its new location at B.

- Example: Name resolution mechanism

- Follow the chain of pointers to reach the entity

- Update the entity’s reference when the present location is found

- Long chains results in longer resolution delays & are prone to failure due to broken links.

Home based ApproachesPermalink

- Each mobile entity has a fixed IP address (home address)

- Entity’s home address is registered at a naming service

- Home node keeps track of current address of the entity (care‐of address)

- Entity updates the home about its current address (care‐of address) whenever it moves

Distributed Hash Table (DHT): ChordPermalink

- Every node is assigned a random m‐bit identifier

- Every entity is assigned a unique m‐bit key

- Entity with key k falls under jurisdiction of node with the smallest identifier id ≥ k , denoted as succ(k)

- How to resolve a key k to the address of succ(k)?

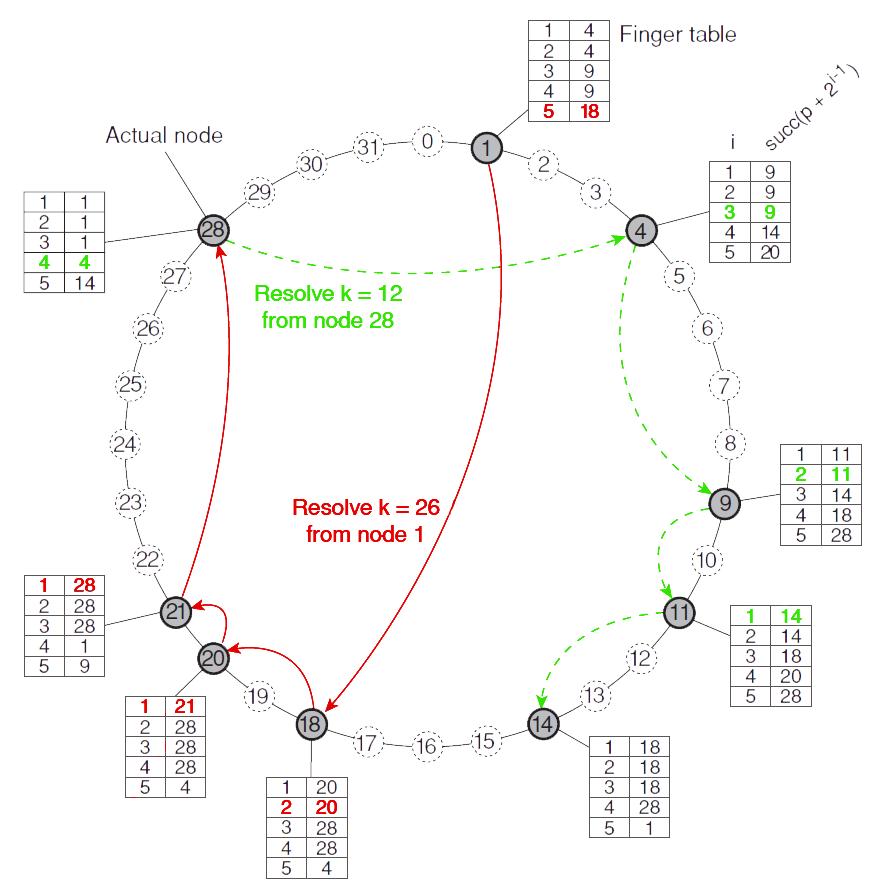

- Each node p maintains a finger table with at most m entries, value of the ith entry is FTp[i]= succ(p+2i‐1)

- To look up a key k, node p forwards the request to node q with index j where q = FTp[j] ≤ k < FTp[j+1]

- If p < k < FTp[1], the request is forwarded to FTp[1]

- A lookup requires O(logN) steps, where N is number of nodes in the system.

- Please refer to the assignment related to Chord OR the example below

Resolving key 26 from node 1 (in red) and key 12 from node 28 (in green) in a Chord system.

Exploiting network proximityPermalink

- Problem: The logical organization of nodes in the overlay may lead to erratic message transfers in the underlying Internet: node p and node succ(p+1) may be very far apart.

- Solutions:

- Topology-aware node assignment: When assigning an ID to a node, make sure that nodes close in the ID space are also close in the network.

- Can be very difficult.

- Proximity routing: Maintain more than one possible successor, and forward to the closest.

- Proximity neighbor selection:When there is a choice of selecting who your neighbor will be (not in Chord), pick the closest one.

- Topology-aware node assignment: When assigning an ID to a node, make sure that nodes close in the ID space are also close in the network.

Hierarchical ApprochesPermalink

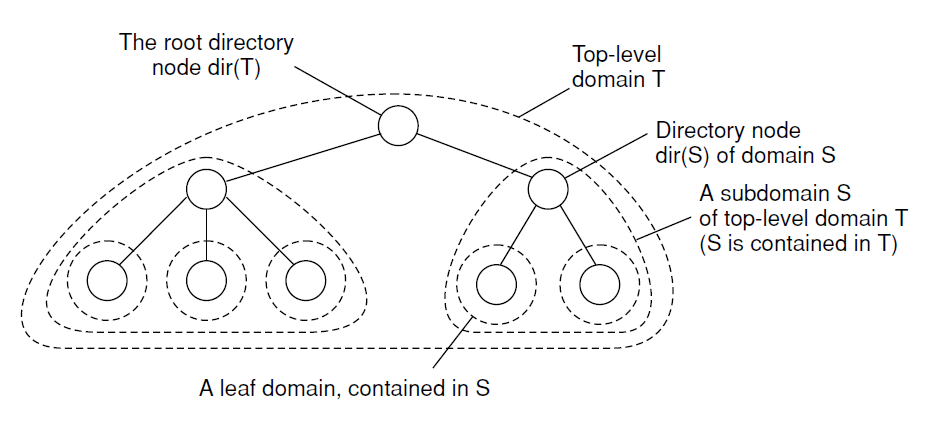

- Large-scale search tree for which the underlying network is divided into hierarchical domains.

-

Each domain is represented by a separate directory node.

Hierarchical organization of a location service into domains, each having an associated directory node.

Structured NamingPermalink

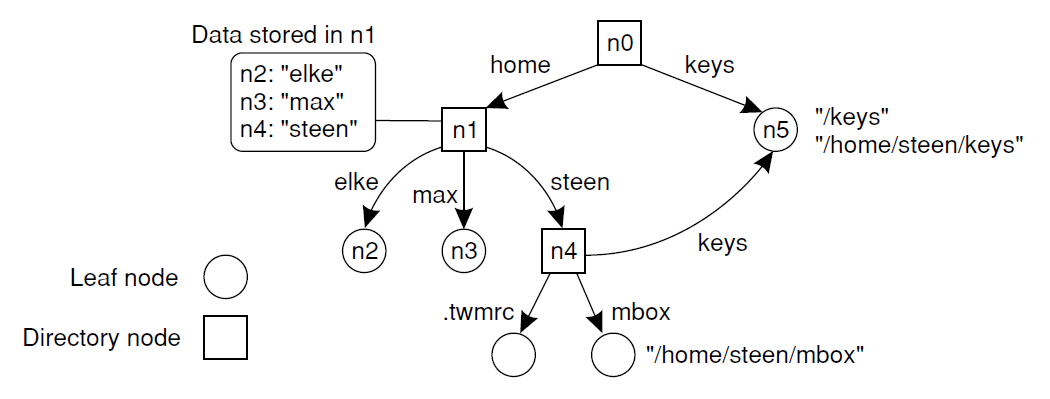

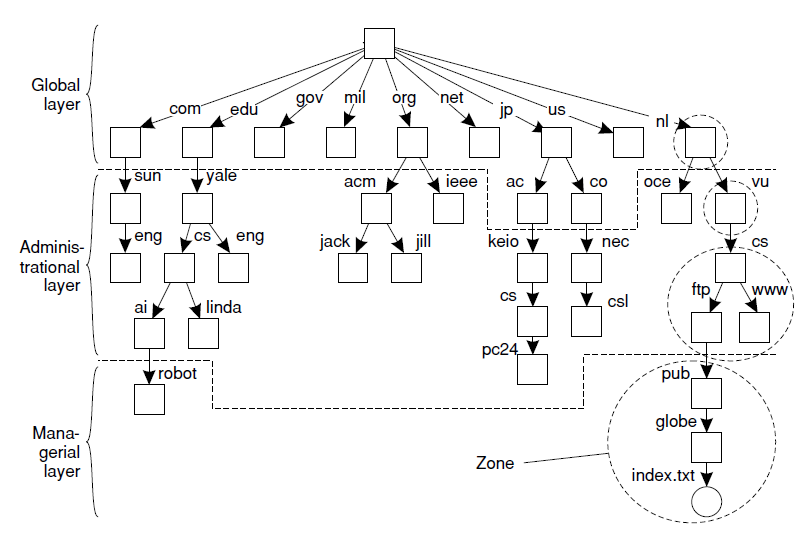

-

Flat names are hard to remember, so human-friendly names are used which are structured and organized into name spaces.

A general naming graph with a single root node.

-

Name Resolution: Process of looking up a name and it’s performed by traversing the graph.

-

Two main approaches to name resolution:

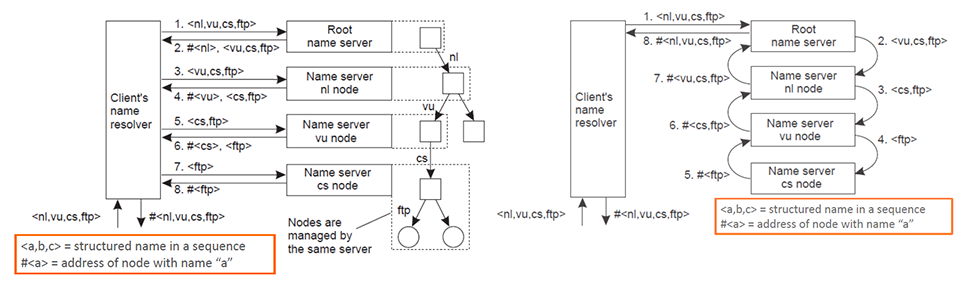

Resolving the name “ftp.cs.vu.nl”. Iterative name resolution (left) vs Recursive name resolution (right)

- Iterative Name Resolution:

- Client’s name resolver sends the complete name to the root name server.

- Root server partially resolves the name and returns the result to the client’s resolver, which then contacts the next name server in the hierarchy.

- This process continues until the complete name is resolved.

- Recursive Name Resolution:

- Each name server passes the partially resolved name to the next name server in the hierarchy.

- The last name server in the chain returns the fully resolved name to the first name server, which then returns it to the client’s resolver.

Iterative vs Recursive

- Iterative involves more steps but less server load.

-

Recursive is more efficient in caching and lowers communication costs.

- Name Space implementation: For a large‐scale distributed system is partitioned into three logical layers

- Global layer: high‐level directory nodes

- Administrational layer: directory nodes managed by a single organization

- Managerial layer: nodes that change frequently

An example partitioning ofthe DNS name space, including Internet‐accessible files, into three layers.

Attribute based namingPermalink

- Also known as directory services

- Entities have a set of associated attributes for searching.

- Attributes can be simple like sender, recipient, subject in an email system.

- Describes an entity in terms of (attribute, value) pairs.

- Naming system returns entities that meet the user’s description.

- Examples:

- In an email system, messages can have attributes like sender, recipient, and subject.

- In a file system, files could have attributes like file type, owner, and date modified.

- Challenges:

- Exhaustive search through all descriptors can be performance-intensive.

- Balancing the load among servers for attribute-based queries is essential.

Synchronisation, Mutual exclusion, Election AlgorithmsPermalink

Synchronization in distributed processes involves:

- Clocks: Identifying when something occurred.

- Mutual exclusion: Cordinate between processes that access the same resource.

- Election algorithm: A group of entities elect one entity as the coordinator for solving a problem.

- Message consistency: Making sure all have the same view of events.

- Agreement: Ensuring everyone can agree on a proposed value.

These aspects are simple in non-distributed systems but become complex in distributed systems.

-

Time Synchronization

- Physical Clock Synchronization (or simply known as Clock Synchronization)

- actual time on computers are synchronized

- Logical Clock Synchronization

- Computers/processes are synchronized based on relative ordering of evenings

- Physical Clock Synchronization (or simply known as Clock Synchronization)

Physical Clock Synchronization or Clock SynchronizationPermalink

- Skew: the difference between the times on two clocks (at any instant)

- Clock drift: counting of time at different rates

- Clock drift rate: the difference per unit of time from some ideal reference clock

- Correction Methods: Not a good idea to set a clock back for message ordering and software development environments.

- Gradual clock correction

- If Fast: The system will slow down the clock until it synchronizes with a reference clock.

- If Slow: The system will speed up the clock until synchronization is achieved.

- Ordinary quartz clocks drift by about 1 sec in 11-12 days. (10-6 secs/sec).

- High precision quartz clocks drift rate is about 10-7 or 10-8 secs/sec

Types of Physical Clocks:

- Quartz Clock:

- It uses a quartz oscillator that typically oscillates at 32KHz.

- The clock drift is around +/- 15 seconds per month.

- Not suitable for large distributed systems due to its drift.

- Atomic Clock:

- Uses Caesium 133 as an oscillator.

- Extremely accurate with a drift rate of 108 ppm.

- Often used in satellites for GPS.

- UTC

Problem

- Sometimes we simply need the exact time, not just an ordering.

- Solution: Universal Coordinated Time (UTC)

- Based on the number of transitions per second of the cesium 133 atom (accurate).

- At present, the real time is taken as the average of some 50 cesium clocks around the world.

- Introduces a leap second from time to time to compensate that days are getting longer.

- Precision:

- Ensure that the time difference between two clocks (from any two machines) is within a certain acceptable range called π.

- Equation:

|Cp(t) − Cq(t)| ≤ π- Meaning: The absolute difference between clock p’s time (

Cp) and clock q’s time (Cq) at any moment ‘t’ should be less than or equal to π.

- Meaning: The absolute difference between clock p’s time (

- Accuracy:

- Ensure a clock’s time is close to the actual or real time (UTC) by a specified range called α.

- Equation:

|Cp(t) − t| ≤ α- Meaning: The absolute difference between the time shown by machine p’s clock (

Cp) and the real time ‘t’ should be less than or equal to α.

- Meaning: The absolute difference between the time shown by machine p’s clock (

- Synchronization:

- Internal: Adjust clocks so they’re consistent with each other (precision).

- External: Adjust clocks so they’re close to the real time (accuracy).

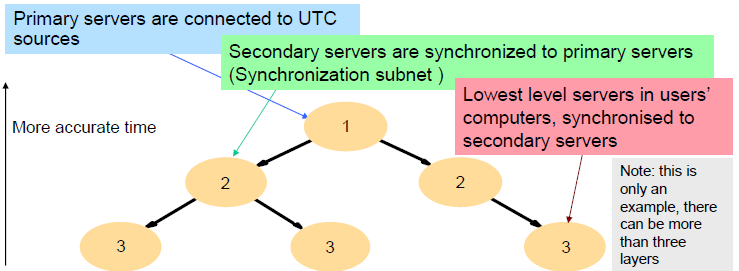

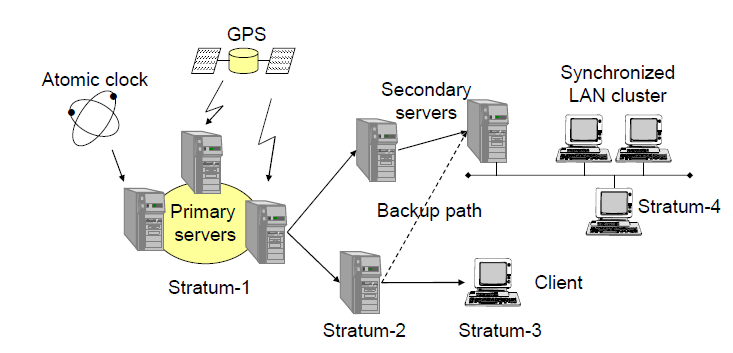

NTP (Network Time Protocol)Permalink

NTP

- NTP is a protocol used to synchronize computer clocks over a network.

- It uses a hierarchical structure of time servers distributed across internet

- Each layer termed as a ‘stratum’. The stratum 0 or 1 (whichever is first) servers are the most accurate and are often connected to atomic clocks (UTC).

- NTP can adjust the time on a system gradually, compensating for latency and jitter, to align with the reference time.

- NTP relies on network communication to achieve synchronization.

- Scalable to large number of clients and servers

-

Authenticates time sources to protect against wrong time data

Levels in the synchronization subtree and exchange of timestamps between servers and clients via UDP

- Modes of synchronization

- Multicast:

- Server in LAN sends time to others, assumes delay. (Less accurate)

- Procedure Call:

- Server takes requests, adjusts time. (More accurate than multicast)

- Symmetric:

- Server pairs share time info.

- Used for high accuracy needs.

- All modes use UDP for time data transfer.

- Multicast:

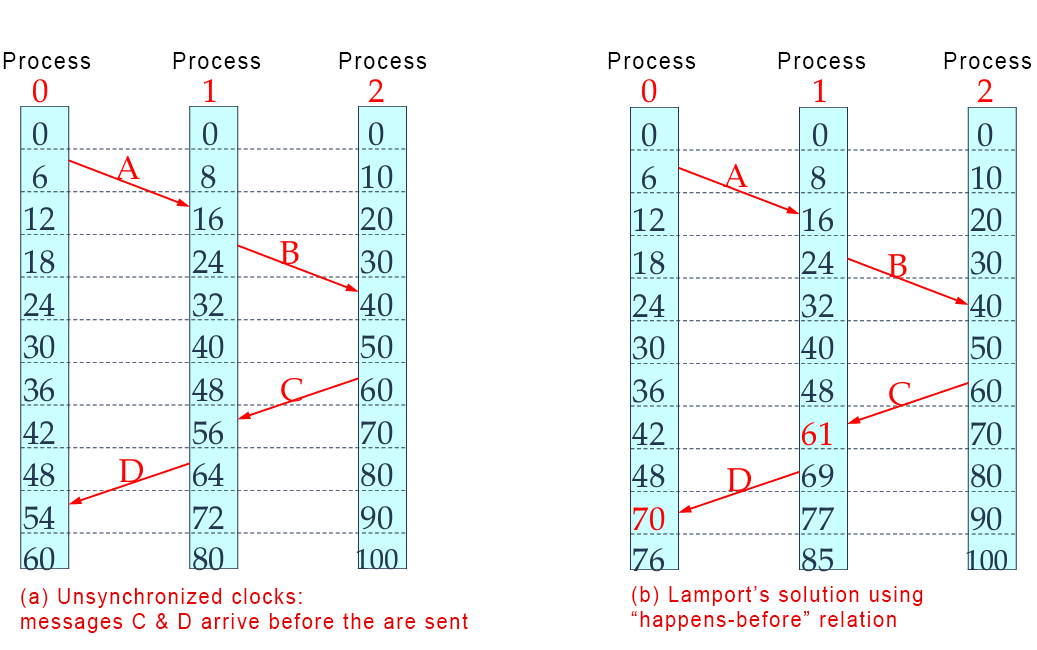

Logical ClocksPermalink

- Happened-before Relationship:

- It’s important that processes agree on the order of events, not the exact time.

- Key rules:

- In the same process, if event a happens before b, it’s a → b.

- If a sends and b receives a message, it’s a → b.

- If a → b and b → c, then a → c.

-

Logical Clocks’s Problem: To keep a global view matching the happened-before order.

- Solutions:

- Use timestamps for events. If a → b, the timestamp of a is less than b.

- With no global clock, use a separate logical clock for each process.

- Solutions:

- Lamport’s Logical Clocks:

- P1 sends a message to P2, including the send time.

- P2 logs its receive time.

- If P2’s time is earlier than the sent time, it adjusts its clock slightly ahead (1 milli second at least).

- If P2’s time is later, no change is made.

-

This preserves the order of message events (“happens-before” relationship).

Example showing Lamport’s algorithm

- Logical clocks adjustments implemented in middleware.

Mutual ExclusionPermalink

- Distributed processes need to coordinate to access shared resources

- Uniprocessor systems use shared variables or OS support for mutual exclusion.

- Not enough for DS. Distributed systems use message passing for mutual exclusion.

Types of Distributed Mutual Exclusion:

Two main categories:

-

Permission-based Approaches: A process wanting to access a shared resource asks permission from one or multiple coordinators. Two types:

- Centralized Algorithms

- Decentralized Algorithms

-

Token-based Approaches:

- Every shared resource possesses a token.

- This token is passed among all processes.

- A process can access the resource only if it has the token.

Centralized AlgorithmPermalink

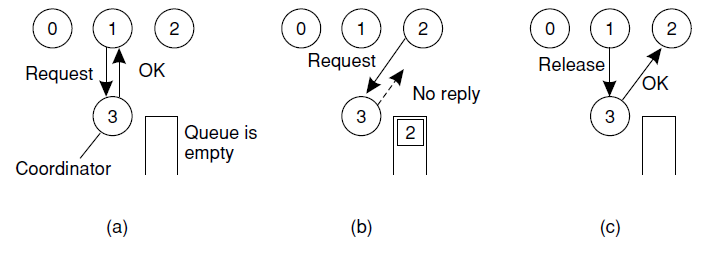

(a) Process 1 asks the coordinator for permission to access a shared resource. Permission is granted. (b) Process 2 then asks permission to access the same resource. The coordinator does not reply. (c) When process 1 releases the resource, it tells the coordinator, which then replies to 2.

Advantages:

- Guaranteed exclusive access by centralised control

- Fair algorithm guaranteeing order of requests

- No starvation of single processes

- Easy to implement

- Only three messages per entry in the critical region

Disadvantages:

- Coordinator becomes a single point of failure and a performance bottleneck

- It is hard to see, if the coordinator is blocked or crashed (in this case, a new coordinator has to be determined)

Decentralized AlgorithmPermalink

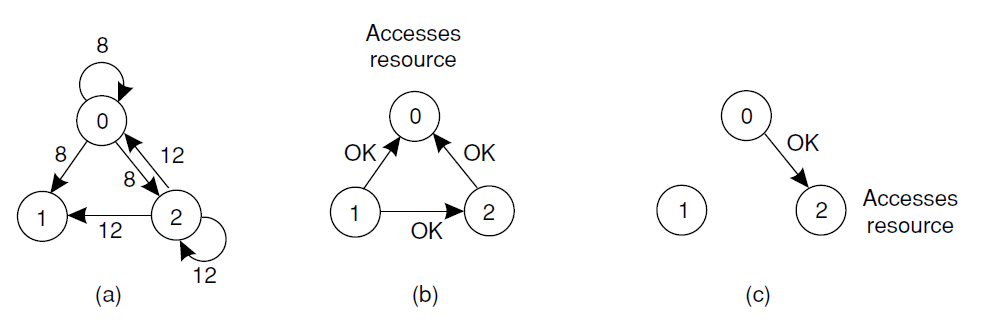

(a) Two processes want to access a shared resource at the samemoment. (b) Process 0 has the lowest timestamp, so it wins. (c) When process 0 is done, it sends an OK also, so 2 can now go ahead.

- Based on a total ordering of event (happens-before relation)

Algorithm:

- To enter a critical region, a process:

- Builds a message: {name of critical region; process number; current time}

- Sends the message to all other processes (assuming reliable transfer)

- When a process receives a request message:

- If not in critical region: sends OK.

- If in critical region: does not reply, queues request.

- If waiting to enter and has a later timestamp: sends OK; else queues request.

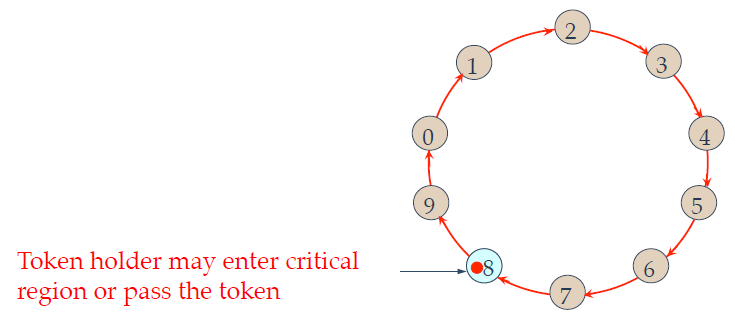

Token RingPermalink

(a) Two processes want to access a shared resource at the samemoment. (b) Process 0 has the lowest timestamp, so it wins. (c) When process 0 is done, it sends an OK also, so 2 can now go ahead.

- Processes are organized in a logical ring

- A unique token circulates in the ring, and a process can enter its critical section only when it holds the token.

- After use, the token is passed to the next process.

- Gurantees mutual exclusion

- No starvation

Comparison of Mutual Exclusion Algorithms (Optional)Permalink

| Algorithm | Messages for Operations | Entry Delay | Potential Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized | 3 | 2 | Coordinator crash |

| Distributed | 2 (n – 1) | 2 (n – 1) | Crash of any process |

| Token Ring | 1 to ∞ | 0 to n – 1 | Lost token, process crash |

- Centralized: Uses a main coordinator. Efficient but can fail if the coordinator crashes.

- Distributed: Messages are sent to peers. If a process fails, it can disrupt the system.

- Token Ring: Processes pass a “token” to enter critical sections. Delays can occur, especially if the token is lost or a process crashes.

Election AlgorithmsPermalink

- An algorithm requires that some process acts a coordinator.

Election by BullyingPermalink

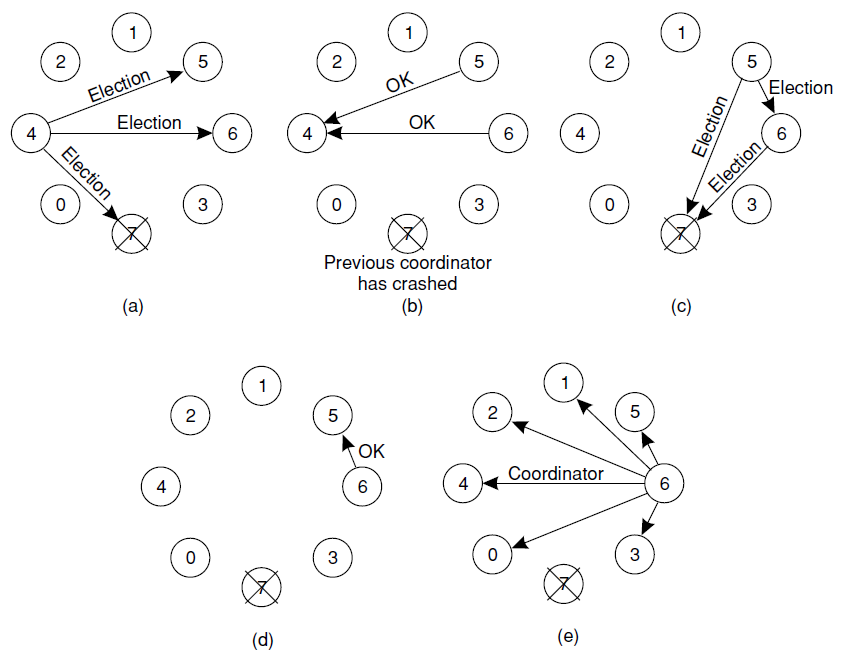

The bully election algorithm. (a) Process 4 holds an election. (b) Processes 5 and 6 respond, telling 4 to stop. (c) Now 5 and 6 each hold an election. (d) Process 6 tells 5 to stop. (e) Process 6 wins and tells everyone.

Algorithm:

- P sends an ELECTION message to all processes with higher numbers.

- If no one responds, P wins the election and becomes coordinator.

- If one of the higher-ups answers, it takes over. P’s job is done.

- Algorithm is named so because the dominance of higher ranked processes over lower ranked ones.

Election in a RingPermalink

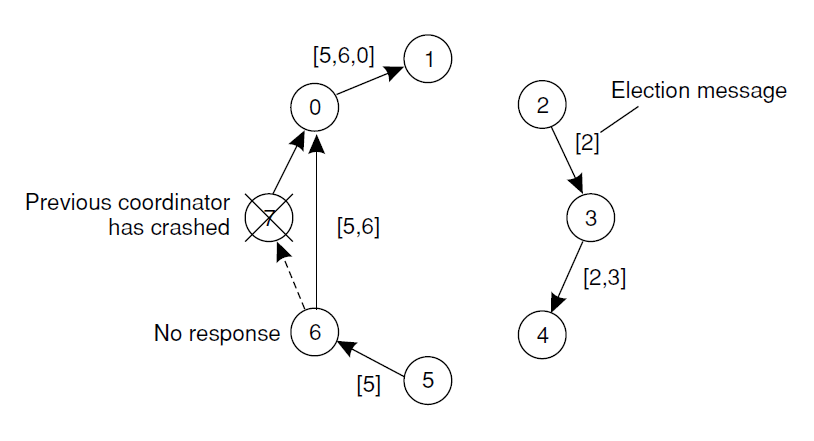

Election algorithm using a ring.

- Processes are physcally or logically ordered in a ring format.

- No token are used

Algorithm:

- Process detects failure, sends ELECTION message with its ID.

- Each process adds its ID to the message.

- Original sender receives message, identifies highest ID.

- Sends COORDINATOR message, sets highest ID as leader.

- All other processes are new ring members.